Features - News Feature

JUNE 18, 2002

Ode to Brooklands

BY WILL BUXTON

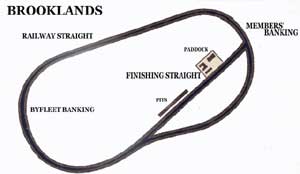

Ninety-five years ago - on June 18th 1907 - the world's first purpose-built motor racing circuit was opened in England. Brooklands, in Surrey, was considered to be one of the seven wonders of the modern age. Today the track is in pieces; the ruins acting as a shattered window to a bygone age. The once majestic banking has been dissected by busy roads, supermarkets and a business park. The people of Brooklands town go about their lives almost entirely unaware of the significance held by the moss-covered monuments, which surround their every waking moment.

|

|||||||

The sheer enormity of the circuit took many by surprise. "Bare figures convey no sense of its stupendous size, and words must fail to describe the impression that the finished track creates at first viewÉin its nakedness, one finds no measure of its size", wrote a journalist for "The Motor".

And so it was that motorsport was born in Britain. For 32 glorious years (give or take a stoppage for World War I) Brooklands existed as Britain's finest motor racing circuit and testing venue. As an oval track, the enormous straights and long, high banked corners enabled cars to run flat out, something that was unachievable anywhere else in Europe at the time. Brooklands became the home of Sir Malcolm Campbell's workshops and it was there that he tested his Bluebird Land Speed Record cars.

With the technological advances made to the automobile in the first 30 years of the Twentieth Century, there was soon the need for a more demanding track. The Outer Circuit was still used extensively, as was the smaller Mountain Circuit, a simple semi-circular track using part of the Members' Banking and the start/finish straight. In 1937 however, the Campbell Circuit was completed. Named after and designed by Sir Malcolm himself, the new circuit was a sign of the versatility of the venue and how, due to its sheer size, it was easy to adjust the circuit to modern needs. However, just two years after the road-racing track had been completed, Brooklands' adaptability would prove to be its downfall.

With Brooklands having such long straights and such a huge infield section it was perfect for young crazy men and their flying machines. In 1908, A. V. Roe became the first Briton to fly in a powered aircraft of his own design, which he did at Brooklands. From then on motor racing and aviation had to work alongside one another at the circuit. The famous Vickers, Hawker and Sopwith aviation firms were all based at Brooklands, as was Barnes Wallis, the man who later went on to invent the "bouncing bomb" used by The Dambusters in World War II.

The Second World War saw aircraft factories bombed heavily and the banked corners made Brooklands easily recognizable from the air and the track was badly damaged. The production of the Hawker Hurricane continued in earnest and it was thanks to the workers in the Hawker factory at Brooklands that enough planes were made to win the Battle of Britain. A huge warehouse was built on the start/finish straight and by 1945 it was in a sorry state.

Hangers and warehouses were scattered down both the Railway and Start/Finish Straights. The banking at the Byfleet end of the track had been sliced open by a road, allowing access to the aerodrome from the West and what else remained of the circuit had been badly bombed.

The track was deemed to be irreparable and was sold to the Vickers Aviation company and continued as a center for until the closure of the British Aerospace premises in 1988.

In 1987, the local Council, which had gained the rights to the old track some years earlier, decided it would sell the land and allow what remained of the track and the motoring village to be demolished. A group of motor racing enthusiasts realized that what remained of the Brooklands track had to be saved and so the Brooklands Museum Trust was born. The track now belongs to them and in 1991 a museum was opened on the site, chronicling the motor racing and aviation history of the venue.

Relying completely on public donations and support from groups such as the BRDC, the Trust is in the process of renovating what remains of the track. The Clubhouse, Motoring Village and old pits complex are kept in magnificent condition, true to the age of splendor in which they were built. The old Test Hill remains one of the focal points of the track and, on foot, is pretty tough to climb. What greets you at the top however is worth any amount of suffering. You will not find a more astoundingly beautiful and yet heartbreaking sight in the entire world.

Walking down a winding dirt track you emerge behind a row of trees. Following the path and pushing the trees out of the way you step onto what was once, the theatre of racing Gods. Rising up before you, like a Roman amphitheater, is what remains of the stunning Members' Banking.

The bottom of the track is flat but as you climb up the rough concrete panels, the gradient becomes steeper and steeper. As your feet slip on the moss and you try to hold your balance it is almost possible to imagine what it must have been like to have driven one of the very first racing cars around this incredible circuit at full throttle. At the top of the banking you can see the track curving and disappearing in front of you, under the reconstructed Members' Bridge, and to the left you can see where the start/finish straight joins the track. It is a spectacular sight to behold.

Looking behind you, there is a chicken wire fence and dense shrubbery. The once majestic banking of the seventh wonder of the modern world starts, as if from nowhere, and a short walk around the banking reveals that where once there was a racing circuit, there now flows a river. It is hard to imagine what this place must have been like when it was opened, but in the broken state in which it now lies, it is maybe all the more striking.

A few years ago I went to the first Goodwood Revival Meeting. It was an incredible day where the atmosphere of a period in racing that those of my age never got to experience, was relived in the surroundings of a track brought back to its former glory. As my day at Brooklands drew to a close I wondered what chances there were of something similar happening to this, the birthplace of British motorsport.

The more I thought about it the more it upset me. The Western banking at the Byfleet end has a road running right through it. A supermarket owns that part of the circuit and the volunteers that I spoke to in the museum were devastated at the condition in which the track had been allowed to fall. The Campbell Circuit is now protected by law but the rights for its use are owned by the Trust.

And then it hit me. It's a bit extreme but all you'd need to do was rebuild the circuit over the river, knock down a few dilapidated warehouses, ask the trendy office blocks if they minded moving back a few hundred meters, cut to the Members' Banking by going up Test Hill and voila, you've almost got the infield circuit back. The men at the museum gave a nodding smile and agreed.

It was wholly impractical, but a lovely dream.

I drove to the supermarket and sat at the top of the banking, quietly reflecting on my day. I looked at the vacant expressions on people's faces as they drove beneath me, through what was once the jewel in not just British, but world motorsport, and wondered if any of them had a clue what this moss covered inconvenience was. More to the point, I wondered if any of them cared. But then I realized that it really didn't matter. The thing was that it mattered to me, and the spirit of Brooklands was raging in my heart. All this from a few hours spent walking around an old piece of concrete?

What an incredible place it must have been.