Features - Technical

NOVEMBER 20, 2000

Chalk and Cheese

BY PETER WRIGHT

Ferrari and McLaren are about as similar as chalk and cheese. And yet, they have each produced a Formula 1 car that, in the hands of the two most skilled racing drivers in the world, perform on average within less than half a percent of each other. To achieve this level of precision between two products from such different organizations, is in engineering terms, remarkable.

In order to assess the ultimate performance of a Formula1 car, one must look to the performance in Qualifying. The objectives in Qualifying and in the race are different. Fortunately, racing cars have very simple objectives, unlike most machines. Even fighter aircraft are a compromise between range, speed, altitude, climb rate, manoeuvrability, serviceability, cost etc. Racing cars just have to achieve the fastest possible speed around a closed circuit. In the race, however, additional factors are involved, such as: starting ability, tire wear, fuel consumption, overtaking ability, driver fatigue, driver motivation, reliability; all of which compromise the ultimate performance. Only in Qualifying is there any chance of assuming that the cars are being driven at their full potential. Only one fast lap is needed and there is no one else to race with on the track. Grid position has enough importance nowadays, that in most cases at least, one can assume the drivers are extracting every last bit of the performance from their cars and trying their utmost for a fast lap.

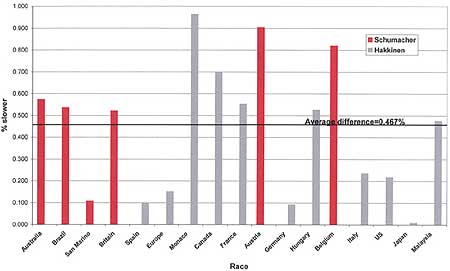

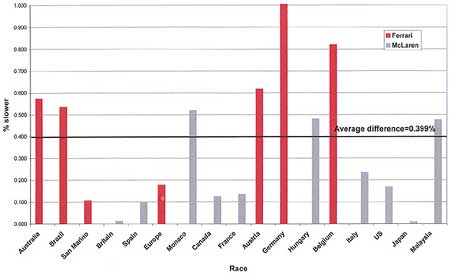

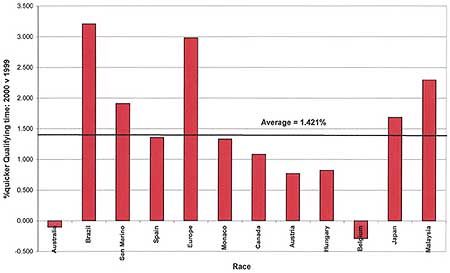

The average also includes Austria and Belgium, where Ferrari temporarily lost their way with the set-up of their car. Either Schumacher or Hakkinen did not always set Pole, so if we take the fastest Ferrari compared to the fastest McLaren, the picture changes to that in Figure. 2. The average performance difference between the two cars drops to 0.399%. In both these approaches, the extraordinary conditions during Qualifying for the German GP show up, as Coulthard managed to set a time nearly 1.5 seconds quicker than any one else. Similarly, Ferrari's resurgence over the last four races is clear.

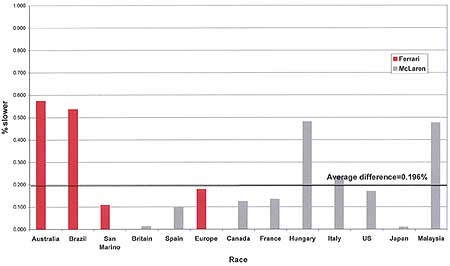

It is evident that the difference in performance between the Ferrari F1-2000 and McLaren-Mercedes MP4-15 is less than half a percent when averaged out over the 17 races of the full season. If we consider only those races where there were no extenuating circumstances and the true ultimate performance was displayed during Qualifying, i.e. take out Monaco (exceptional driver performance), Austria and Belgium (Ferrari loses way), and Germany (weather), we end up with Figure.3, and the average difference in performance is now down to 0.196% - less than one fifth of one percent. Ferrari was quickest in 70% of these Qualifying sessions. Even if we include all the events, Ferrari was still quicker in nearly 60% of them - which tends to contradict the commonly held view that McLaren actually had the faster car.

Ferrari and McLaren are two teams that are about as different as one can get in Formula 1. The only similarities are that they are both at the peak of performance and have adequate funding.

Ferrari stands for all the passion that Italians have for fast cars. Involved in racing throughout the 50 years of Formula 1, Ferrari carries the standard for the Italian motor industry and can call upon any part of it for assistance in its racing endeavours. Part owned and heavily backed by Fiat, Ferrari has the technical resources and backup of its parent company's motor and aerospace industries, backed by the universities and research establishments that support them. For years, Ferrari concentrated on engines and this approach brought success until the 70s and 80's, when the British Formula 1 teams (garageistes, as Enzo Ferrari was wont to call them) changed the game to one of chassis and aerodynamics. Importation of British Formula 1 technology, via Harvey Postlethwaite and John Barnard, brought only moderate success, and it was not until the hierarchy of Luca di Montezemolo as President, Jean Todt as Team Manager, Ross Brawn as Technical Director, Rory Byrne and Paolo Martinelli as Chief Chassis and Engine Designers respectively, and Nigel Stepney as Chief Mechanic, all welded together by the motivating flame of Michael Schumacher, that the potential of the technical resource and skilled Italian craftsmanship bore fruit again.

McLaren, in contrast, was one of those British garageistes, created by New Zealander Bruce McLaren in 1966, sharing the World Championship laurels in the 1970s with Lotus, Tyrrell and Ferrari. However, the current McLaren organization was not established until 1980, when Ron Dennis took over. Success was not long in coming, delivered by a series of top chassis designers, engine suppliers and drivers, and fuelled by solid sponsorship and technical partnership deals. Ron Dennis invented the modern Formula 1 corporation. However, the loss of Honda, Ayrton Senna and Marlboro within a few years resulted in a fallow period from which McLaren only really emerged in 1998. Now part owned by Daimler-Chrysler, who also supply Mercedes engines through another Daimler-Chrysler company Illmor, McLaren has Adrian Newey (successfully enticed away from Williams), two drivers who have formed Formula 1's longest lasting driver pairing, and it is back on top.

McLaren has benefited from the British motor sport industry's ace card: the rate at which technical personnel swap about among the UK teams, spreading and spurring on the development of new technologies. In particular, it attracted key personnel from the technically superior Williams team in the mid and late 90's. However it's engineering hierarchy is organized somewhat differently from Ferrari's. Adrian Newey fulfils part of both Ross Brawn and Rory Byrne's roles at Ferrari. He controls overall technical and design direction while McLaren provides an engineering management system directed by Martin Whitmarsh, recruited from British Aerospace, relieving Newey of many of the day to day administrative tasks handled by Brawn. However, as a result of the split responsibilities and the need to attend most races, Newey must divulge much more of the design to the other designers and researchers at the factory than Byrne, who goes to few races. Mario Illien heads McLaren's engine supplier, Illmor. Although from a separate organization, Illien has worked closely with Newey at Leyton House before joining forces again at McLaren; the relationship is pretty close. Ross Brawn is in complete charge at races, and determines strategy. Just who makes the final race decisions at McLaren is not clear, but it is apparently much more of a consensus process.

Comparing organizations and the backgrounds of the key technical people gives no clues as to how they create two such similarly performing vehicles. Mercedes' and Fiat's range of road cars (Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Lancia and Fiat) are dissimilar. Only in their white van and truck ranges do the two producers compete directly. Both parent companies are however in the aerospace business. Brawn is as cunning and systematic as a fox - he could easily talk the motor racing equivalent of a piece of cheese from the beak of an old crow. He has won Le Mans with Jaguar, and knows that to finish first, one must first finish. Newey is one of the first of the current breed of motor racing engineers. He gained his knowledge of aerodynamics at university (Southampton - one of the first to provide a course suited to motor sport) and gained a practical insight into what it takes to make a car fast by race engineering Bobby Rahal's CART car. He knows what he wants in a car, but is prepared to work with a team of technical experts to establish that his vision is perfected. South African Rory Byrne started his working life as a chemical engineer, but an enthusiasm for cars led him into motor racing engineering and design. His cars have always been somewhat idiosyncratic and often faster than expected. Since pairing up with Ross Brawn at Benetton, he has produced consistently quick and reliable cars.

Even the key engine designers have followed radically different routes to their current positions. Paolo Martinelli was born and bred in Modena, and steeped in the legend of Ferrari from an early age. Educated at the University of Bologna, down the road from Ferrari, he has worked at the company ever since joining them on graduation. Moving from head of Ferrari's road car engine department to take charge of racing engines in 1994, he took an analytical approach to engine design and produced Ferrari's first V-10, to the horror of Ferrari V-12 purists. His engines have been powerful and almost bullet proof, if not the smallest and lightest. In contrast, Swiss-born Mario Illien started his engine design career designing diesel engines for tanks. After he had gained experience of the design of racing engines at Cosworth, he and Paul Morgan started Illmor with the support of Roger Penske and Chevrolet, to supply engines for the CART series. Graduating to Formula 1, he met up with the people from Mercedes while supplying engines to the Mercedes supported Sauber team. Mercedes eventually took over Chevrolet's interest in Illmor, and the Mercedes-Illmor Formula 1 V-10's have consistently been the smallest and lightest engines. As powerful as the best, McLaren's engines have at times proved fragile at crucial stages in the season.

One cannot ignore the contribution of the drivers to the development process. While Hakkinen has never unduly concerned himself with the technical aspects of the car, Schumacher has. However both drivers drive at the limit most of the time, even during testing and that, plus unambiguous feed back, is the most valuable contribution a driver can make to development. McLaren had a superb test driver in Olivier Panis; Ferrari has Fiorano for testing at any time.

One reason the cars are so close is that Formula 1 is in the middle of a period of technical stability. The key performance parameters, weight, power, tires aerodynamic downforce, and aerodynamic drag have not had their performance limiting regulations significantly changed for a couple of years. All teams can build a car down to the weight limit of 600kg, including the driver. There is some advantage in reducing the weight of the car itself, and using strategically placed ballast to lower the CG and trim the fore and aft weight distribution. Both Ferrari and McLaren have the contacts and resources to exploit the most advanced aerospace materials and do so.

The V-10 engine is reaching a critical point in its development. Both Ferrari and Mercedes engines rev at over 18,000rpm. These RPM figures are up at the level where they present problems with torsional harmonics. Alternative materials for the crankshaft, which would raise its natural frequency through being stiffer and lighter, are banned by the regulations. So are V-12s. With an RPM barrier, it is hard to gain much more power. The great advances in engine size and weight have been gained by net machining engine castings (i.e. CNC machining all over) and significant further gains are going to be hard to come by. The two competing engines have pretty well the same performance.

Not only do the two cars run on the same tires, but also the tire specification has been stable for two years, with four grooves in each tire. Because there has been no tire competition for a couple of years, Bridgestone have supplied fairly hard compounds and both teams have been able to develop their cars around these tires. Some variation must arise from the individual choice of compound at each event, for Qualifying and race. From next year it will be different with the arrival of Michelin. Although both Ferrari and McLaren will be on Bridgestones, tires will undergo continuous development and the cars will have to follow the changes i.e. the situation will be less stable, and differences in performance will occur from time to time.

The greatest difference between the two cars lies in their aerodynamic performance. Newey has for some years now concentrated on giving his cars low pitch sensitivity. This enables them to run softer suspension springs, giving excellent curb hopping ability. Byrne's cars have traditionally been run pretty stiff, though I suspect that pitch sensitivity is an area that has been concentrated on since Ferrari's new wind tunnel has come on line. Ferrari's markedly improved performance relative to McLaren at Monza this year, probably had more to do with the elimination of the curbs, over which McLaren had always excelled and so been able to take a straighter line through the chicanes. It is impossible to quantify the differences in downforce and Lift/Drag ratio. It would seem that they are not so different now.

The final piece in the performance puzzle is set-up - the ability to tune the car to achieve its full performance potential. Testing on GP circuits before the event enables teams to arrive at a GP with the car already set up to perform at its optimum. Ferrari explained their poor performance at Spa and the A-1 Ring on not being able to test there. Perhaps the Ferrari is "peakier" than the McLaren, and it takes a little longer to get it set-up on that peak. The McLarens seem to have a broader performance plateau and works everywhere, which would be a characteristic of less pitch sensitive aerodynamics and softer suspension.

|

|||||

Is the fact that the performance of the cars is reaching a peak determined by the constraints of the regulations, sufficient to explain the closeness of the two championship contenders? I do not think so.

Even Ferrari and McLaren, with all their precision manufacturing and quality control procedures, are hard pressed to build two identical cars that would perform within one fifth of a percent of each other in the hands of the same driver, i.e. 0.140 seconds in a 70second lap. Drivers always prefer one particular chassis to another, and how many times does one hear the excuse "I had to use the spare and it wasn't as good as my normal car"?

A few years ago, Chrysler published some information on the variability of Lamborghini Formula 1, 3.5l, V-12 engines, Lamborghini being at that time a subsidiary of Chrysler. They stated that their target for the consistency of the performance of engines built to the same specification was ±1.5% i.e. ±12 PS in 800. Illmor and Ferrari probably do better than that now, but it is some indication of tolerance levels between individual builds.

I do not believe that the closeness in performance of the two cars can be explained in engineering terms - they are too close for that. Instead I believe one must turn to psychology for the explanation, a much less precise science than engineering! What Ferrari and McLaren have undoubtedly achieved is to provide each of their drivers with cars that are very evenly matched so that they are able to compete on just about equal terms on most circuits throughout the season. Psychologically, the drivers know that it is up to them; they can no longer blame the equipment if they are slower. Add to this the fact that motor racing is a sport where only relative performance matters, not absolute performance. There are no extra points for beating one's opponent by one minute, rather than a thousandth of a second. Drivers spend most of the time during Qualifying, when not out on the track, scrutinizing the other driver's times. Even when they are out on the track, most of the Pits-to-car radio traffic is about other people's times. It is a well-known "fact" that a car on Pole handles beautifully, but the moment its time is beaten, the handling becomes rubbish. I suspect that the closeness between the Ferrari and McLaren, driven by any of their four drivers, is a function of the small margin necessary to achieve Pole position. So often we see a driver step up his performance only when the opposition improves on his time. This is the psychological factor that makes Qualifying on occasions such a good spectacle.

Sometimes there comes along a driver to whom absolute performance is as or more important than relative performance. I believe Ayrton Senna was such a driver. For whatever personal reasons, he wanted to know where his own limits lay. It was this aspect of his character that sometimes enabled him to far out-qualify everyone else, even those in equal or superior cars. Such a time was at the US GP in Phoenix in 1991; he took Pole in his McLaren-Honda by over 1.1 seconds - more than 1.35% faster than Prost in his Ferrari. I did not really understand this until Johnny Herbert explained it to me at the 1992 Monaco GP. He and Mika Hakkinen had been in the lower half of the grid for most of Qualifying, posting almost equal times and complaining about the handling of the Lotus T107. In the last few minutes Johnny went out and elevated himself to 9th on the grid, leaving Mika down in 14th. He arrived back in the Pits, having knocked more than half a second off his time, with a look of total satisfaction on his face. Prompted to explain this sudden change in pace, he told us that he had "Édriven the car from several car lengths ahead of it, and just let it follow." He then added, "Now I know what Ayrton meant." Just occasionally one sees a driver come in with a wide-eyed look of awe, which later turns to quiet, inner satisfaction. Only then can one believe that the car has been driven to its absolute limits, and its true ultimate performance been demonstrated.

The only way I can think of by which one could compare the ultimate performance of two such equal cars as the 2000 Ferrari and McLaren would be to make a regulation that said that, if the World Championship was settled prior to the last race, the two leading drivers must swap cars for the last race. Now that would be interesting!