Features - Feature

AUGUST 14, 2003

The pioneer

BY JOE SAWARD

Take a walk through the gardens at the Porte Maillot in Paris and you will find a large memorial to a man called Emile Levassor. Some people may know him as the partner of Rene Panhard; others may know him as a great automotive innovator but very few will ever have heard of his exploits as a racing driver.

Take a walk through the gardens at the Porte Maillot in Paris and you will find a large memorial to a man called Emile Levassor. Some people may know him as the partner of Rene Panhard; others may know him as a great automotive innovator but very few will ever have heard of his exploits as a racing driver.

Levassor, however, not only won the first proper motor race in history but also laid out what became the normal layout for all the automobile designers who followed him.

Born in the country to the south of Paris, the son of a farmer, Levassor studied engineering at France's most famous school, the Ecole Central, and then went into industry. In the early 1880s he met a Belgian lawyer called Edouard Sarrazin who was a patent expert and who had decided to invest in a little-known German engineer called Gottlieb Daimler, in exchange for the French rights to any engine that Daimler produced.

Levassor moved on to join a precision engineering from which was being run by Rene Panhard, a former classmate from the Ecole Centrale and when Panhard's partner died in 1886 the company became known as Panhard & Levassor. At the same time Sarrazin convinced Levassor that the firm could make money building Daimler's engines. Sarrazin died soon afterwards but his widow Louise took over the patent business.

In 1889 the French decided to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, with an Exposition Universelle, which was open for six months between May and November. The centerpiece of the exhibition was Gustave Eiffel's extraordinary tower which dominated the exhibition halls in the Champ de Mars but inside the halls were a stunning array of exhibits, which attracted an amazing 28m visitors.

One of the stars of the show was an automobile constructed by Daimler, featuring the V2 four horsepower gasoline engine which Panhard & Levassor were building.

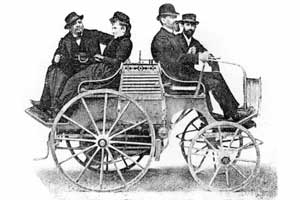

The exhibition created great interest and as demand grew for the engines so Levassor, who was fascinated by the idea of building an automobile, was able to begin experimental work for the company's own vehicles. The first Panhard & Levassor appeared from the workshops in the Avenue d'Ivry, in the south-eastern suburbs of Paris, early in 1890, shortly before Levassor married Sarrazin's widow. The first vehicle went through a series of developments before Levassor settled on the best design. Initially he build a mid-engined device with the driver and three passengers seated back-to-back above the V2 Daimler engine but he soon realized that it was a much better idea to mount the engine in front of the driver and use a mechanical system of transmission to drive the rear wheels. This lowered the centre of gravity, allowed for a bigger engine and increased the stability of the car by lengthening the wheelbase.

The "systeme Panhard" would become the model for all automobiles for many years to come.

In the years that followed that basic design was improved and a gearbox developed and in 1894 Panhard & Levassor did well on the Paris-Rouen Trial. Panhard finished fourth and Levassor fifth but were beaten by the steam-powered De Dion-Bouton tractor of Georges Bouton and by two Peugeots. But the judges ruled that the De Dion-Bouton steam car was impractical and that the Peugeots were powered by Panhard-built engines and so decided that the first prize should be shared between Panhard and Peugeot.

The first real motor race took place in June the following year, organized by the new Automobile Club de France. It stipulated a race from Paris to Bordeaux and back again, a distance of 732 miles. There were 46 entries and after nearly 49 hours of driving Emile Levassor came home the winner at an average speed of 15mph. He was nearly six hours ahead of the next finisher and 11 hours ahead of the car in third.

The success, although later taken away on a technicality, launched Panhard & Levassor as a major player in the automobile world. As production increased so did demand for automobiles and competition for the new market. Levassor worked flat out to develop his cars. As the cars became faster and faster the racers were faced with a new problem. They needed brakes as the wooden blocks used on horse carriages were not sufficient to slow the new automobiles.

Ironically, by making the cars go faster Levassor helped in his own undoing. In September 1896 he took part in the Paris-Marseilles-Paris race. He moved into the lead but just after passing through the village of Lapulad, 15 miles to the north of Orange on the RN7, he was going at high speed down a hill when a dog leapt into his path. He swerved and the top-heavy vehicle rolled. Levassor and his riding mechanic d'Hostingue were both thrown out, Levassor suffering chest injuries when he hit the steering tiller. The pair were able to get the car going again and Levassor drove on to Avignon but there was forced to give up because of the pain.

He suffered a smashed rib and internal injuries and he remained tired and weak in the months that followed. He refused to stop working and was in the process of designing a magnetic clutch when he suffered a coronary embolism while at his drawing board in April 1897. He died immediately. He was 54.