Features - Exclusive Interview

OCTOBER 2, 2000

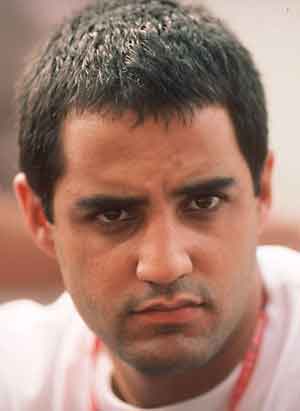

Juan Pablo Montoya: Is he the man who will topple Schumacher?

BY DAVID TREMAYNE

He doesn't say very much outside of the garage. Point of fact, he's deemed arrogant because of his apparent reticence. And that's just in ChampCar circles, where the atmosphere is laid back enough that most drivers feel sufficiently relaxed to spend a little time chilling out with the media. So wait until he gets to F1, some say, and he'll make even Michael Schumacher and Mika Hakkinen seem talkative in comparison.

But American observers are only saying such things about Juan Pablo Montoya in passing, as a color postscript to the accolades they have been busy heaping upon him. What they are saying up front is that the 25 year-old Colombian is the guy who is really going to give Schumacher the works.

Since Hakkinen's maiden GP success at Jerez in the final race of 1997, he has been the only racer consistently able to challenge the man who took over Ayrton Senna's mantle as the F1 yardstick by which drivers are judged and by which they judge themselves.

Had Hakkinen's McLaren not expired due to engine failure just as he had slashed a hefty deficit to Schumacher to fewer than four seconds in the recent USGP at Indianapolis, the story of this year's world title fight might have been a little less predictable than it seems. But it would still not have done anything to change F1's current status quo.

What it needs most right now is somebody to challenge the over-reiterated script of Schumacher v Hakkinen. And that just might be Montoya, who stood quietly in the pits and watched Schumacher speed to a crushing 42nd victory on what now seems an inexorable collision course with Alain Prost's all-time tally of 51.

There has been no shortage of candidates for the irksome moniker of The Next Senna. Jarno Trulli and Jenson Button, the former kart stars who seem to have a propensity for colliding with one another of late, have both been saddled with it. For a while Alex Zanardi was a possible contender after three brilliant years of IndyCar racing in America. Now it is Montoya's turn.

The charger from Bogota has some strong credentials. He won countless races and titles in karting, starting at the age of six and becoming national champion in the children's division in Colombia before he'd reached double figures. Skip Barber courses confirmed his latent talent, and by 1994 he had finished third overall in the Barber Saab Championship. There was a similar result in Europe the following year, in Formula Vauxhall. A year of British F3 set him up for second place in the FIA International F3000 Championship, and he won the title in 1 998. Those who saw his ability to find overtaking places during the F3000 race at Monaco, of all places, still speak in awed tones. He took over Zanardi's seat at Target Ganassi Racing in 1999, and his role as CART's pacesetter, dominating the championship last year in his rookie season. Seven pole positions and seven wins made him the youngest champion ever.

This season he has three times made a winner out of Toyota, whose engine had hitherto been deemed uncompetitive, and taken six pole positions. In May, when Ganassi switched temporarily to the Indy Racing League in order to compete at the legendary (and still prestigious) Indianapolis Motor Speedway, he dealt almost contemptuously with the opposition to win the Indy 500 with insouciant ease at the first attempt.

Gordon Kirby is not given to hyperbole. But the hard-bitten journalistic doyen of the American circuit has seen enough race drivers in his three decades of covering the sport to know what makes a good one. And he has no doubts about Montoya.

"He is the best I have ever seen. And that includes Gilles Villeneuve and Keke Rosberg, who were the best road racing F1 drivers I watched in north America," Kirby insists, and if you think about it such words carry significant impact. Better than Villeneuve and Rosberg, who waged a tough, merciless yet fair war during their sensational Formula Atlantic days? "Montoya drives an oversteering car just like Gilles did," Kirby continues, "but he is more in control of it. He's not wild and crazy, he just hangs it out. I guess you'd say that he is out of control but at the same time in control, he's always super smooth." Villeneuve, remember, was once described by Rosberg as, "the maddest bastard I ever knew."

Montoya's peers in ChampCars also hold him in high esteem.

"Watch out," Max Papis warned at Indy, "because the guy is fast."

"I think that Juan does possess a lot of characteristics that are desirable for a Formula One driver," Gil de Ferran said. "He is talented, and although his personality makes him very insular, it is probably a good trait to have."

Sir Frank Williams finally got around to announcing at Indianapolis what the world has known most of the season: that Montoya will 'replace' Button at BMW Williams in 2001 as partner to Ralf Schumacher. The German is no slouch himself, but Kirby is not alone in feeling sorry for him. Montoya, they say, is going to get inside his head right from the start.

|

Much has been made of the fact that Montoya's arrival is pushing Button off to Benetton/Renault for the next two seasons, as if the young Englishman has been ousted. This is what really happened:

Montoya was Williams' test driver in the 1998 season, when the team still employed Jacques Villeneuve and Heinz-Harald Frentzen. But there were problems in slotting him in alongside newcomer Ralf Schumacher for 1999, although Williams thought very highly of him. "My partner Patrick Head and I felt that we would make every effort to secure Juan," Williams admitted at Indianapolis. "And that has happened. Regrettably, I want to state, at Jenson Button's expense. And Jenson is going to be another great driver. We're sad he's had to go elsewhere for a period of time," - Button is contracted to Williams until 2005 - "but we had already made an unspoken commitment to Juan and we didn't intend to back out of it because suddenly it was inconvenient."

Montoya, of course, was contracted to Ganassi Racing for 2000, hence the need for a driver to stand in for a season. Originally it was going to be Bruno Junqueira, until Jenson's undoubted pace in testing and a final shoot-out proved conclusive.

"It's very simple," is how Sir Frank tells it. "We had begun to talk to Ralf Schumacher for 1999 and Ralf had spent his first 18 months in F1 driving for Eddie Jordan, and flying off the road. There were two theories; either he didn't know what he was doing or he was just exploring the limits. And in the last half of the year, about the time we became interested in him in 1998, he was putting in some steady, sensible and fast drives. We didn't go for Juan for 1999 only because Ralf had two years of critical experience. It was such a close decision, but that fixed it.

"We hadn't made a firm decision to hire Juan Pablo for the 2001 season before we hired Jenson for this season but I repeat, we had a verbal commitment. And Jenson and his management knew the way the contract was constructed. There was no sleight of hand."

Williams is deliberately playing down his expectations of Montoya, but F1 team owners are most definitely not sentimental creatures and the Colombian will be expected to race hard and to win the moment he gets a BMW Williams capable of beating McLaren-Mercedes and Ferrari. "Clearly he is a very talented driver and I don't think he's done anything but learn and improve by racing over here (the States) for two seasons," Williams says. "These cars, after all, have 900 horsepower which is embarrassingly more than we have. Beyond saying those words, no-one can be exactly sure what his achievements may or may not be. And whether we all like it or not, all drivers' achievements are covered by the team and its equipment; and his success will be very much a measure of our possible success. I think it will be exciting to watch that."

Sir Frank rates his team's chances in 2001 of beating the top two as: "Very modest, going down to slim." But that is typical. During the winter of 1999 he and BMW were suggesting that they might be lucky to qualify in the top 10 in 2000, and here they are third in the Constructors' championship&Mac226;"

Equally, he is protective of Ralf, who has done a great job for the team in his two years there, and refuses to overblow Montoya's reputation. Of course he hopes that he will be as quick or quicker than the German, but adds: "Every team principal who signs up a driver hopes he's acquiring somebody who's better than his present incumbents. But there's no telling. It's not really on my mind right now."

Zanardi's return to F1 with Williams promised so much yet was a failure for a complex and inter-related series of reasons that were certainly not all connected to his undoubted ability, so success - even outstanding success - in one category does not necessarily guarantee it in another. In an FW21, which worked, Alex would have looked a very different driver than he did in the lamentable FW20, which didn't. When he and Montoya tested an interim FW19 at Barcelona in 1999, they were pretty evenly matched, though Williams personnel have since attempted to suggest - contrary to their revelations at the time - that the two were not running identical configurations. But Sir Frank's reticence notwithstanding, Montoya appears to have had all the right credentials thus far. He has won on all types of circuit, including the tough ovals where lap speeds reach 240 mph. His ability to control a sliding car on cold tires has long passed into ChampCar folklore. What's perhaps most impressive of all, he hasn't been crashing while crushing. He came together with Michael Andretti in Motegi in Japan early in 1999, in a silly bit of tit-for-tat racing, but other than that he has been as good as gold. When you consider the art of racing, both on the short and the long ovals, which have caught out many an established racer including Nelson Piquet, Nigel Mansell and Zanardi, that speaks volumes. His style may set seasoned observers' nerves on edge on the ovals - where at the time of writing he had led 716 laps in 2000 alone, the fourth highest tally for any driver in CART's history - but his rivals have nothing but praise for his driving ethics. You can run close to him without fear of him trying to intimidate you out of a confrontation, they say.

"I'd hesitate to say that Juan is better than Ayrton Senna," Kirby concedes, albeit with a hint of reluctance in his voice. "But he is certainly in that category, and he is better than Michael Schumacher."

More than one much-vaunted hotshoe has cooled rapidly at F1 level, especially on today's grooved tires which do not let an oversteering driver enjoy anything like the liberties he had cane with slicks, but it's all food for thought for the man who looks increasingly likely to wear this year's crown. And not just because of the challenge that he may face from the Colombian, but because of what may lie in wait for his younger brother, too.